You’d be hard-pressed to find an industry that has not felt the strong impact of design thinking. Automotive, healthcare, entertainment, retail, food and beverages are but a few examples of industries that for decades have been applying design thinking principles to spur innovation, foster creativity, and better meet the needs and demands of consumers. Of course, the tech sector is no exception, as exemplified by Adnovum: Design thinking plays a substantial role in our innovative endeavors, such as conversational AI, and is routinely used in the development of our state-of-the-art applications.

However, with its focus on the individual, design thinking is capable of more than addressing the concerns and needs of consumers and users. Its human-centered approach predestines it as a powerful instrument in tackling humanitarian issues and rising up to socioeconomic challenges, for example, in education, waste management, and scientific research. A case in point was experienced by Stefan Strebel, Expert Requirements Engineer with Adnovum, who traveled to Guatemala to put the design thinking toolbox to use in the fields of horticulture and nutrition

|

|

After attaining my CAS in Design Thinking at Strategic Design ZHdK, I seized the opportunity to join a study trip to Santa Catarina Palopó, a small municipality on the shores of Lago Atitlán in southwestern Guatemala. Mona Mijthab, lecturer at ZHdk and founder of Mosan Sanitation Solution, an organization committed to improving sanitation in low-income regions, as well as Omar Crespo Cardona, founder of Link4 Guatemala, which specializes in applying design thinking methods to effect social change, organized this project. We immersed ourselves in the local culture and socioeconomic reality with the ultimate goal of collaborating with local innovators via the design thinking approach to tackle contextual challenges and design educational concepts and strategy frameworks while. All this while overcoming cultural and language barriers. |

Design thinking theory and practice

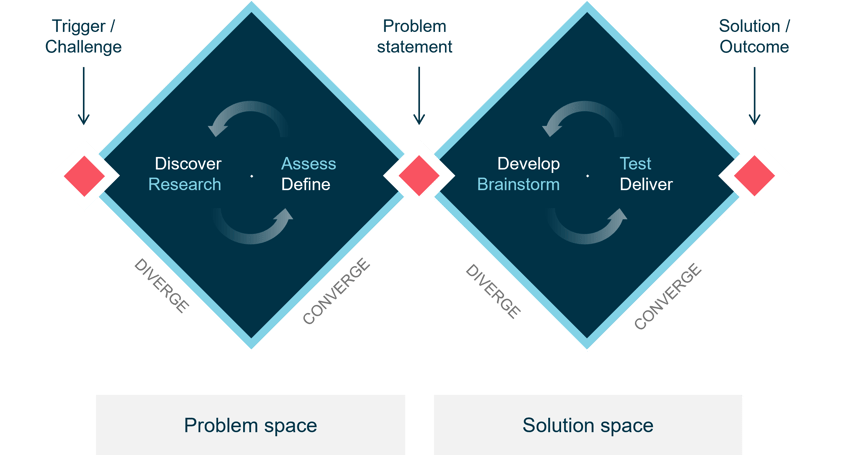

The first theoretical foundations of design thinking date back to the 1930s, and the term itself originated in the 1950s, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that the company IDEO, in particular a televised demonstration of their creative process, introduced the practice of design thinking to a wider audience. The hallmarks of this creative philosophy are iterative, non-linear processes that place great emphasis on cooperation – not only among experts from various fields, but also between the creators and the targeted consumers. This is achieved with an open mind for discovering the true issues at hand, a mentality of unfettered creativity and experimentation, and a constant consideration of the user’s perspective. These concepts are illustrated particularly well in the «double diamond» diagram, a concise summarization of a design thinking approach devised by the Design Council:

Double diamond model of the Design Council

The opening axes of each diamond indicate the exploratory nature of the first steps in each space: design thinkers gather as much information as possible and examine the challenge from a multitude of perspectives to get to the bottom of a problem; the creative phase starts with gathering as many ideas as possible before closing in on a satisfactory solution. But these procedures are not a one-way street. Design thinkers may realize that the defined problem is merely a symptom of a more fundamental issue and reexamine the situation, while solutions can be refined continuously or reinvented entirely.

Another influential process of design thinking stems from the Institute of Design at Stanford, which – broadly speaking – consists of the steps «Empathize – Define – Ideate – Prototype – Test».

Stanford model

Stefan’s project in Guatemala is a textbook example of how a design thinking project is conducted according to the Stanford model.

Empathize

|

Staying with a guest family really helped us absorb the culture and lifestyle in Guatemala. Of course, living standards are different and a reminder that things like unlimited access to running water, which westerners often take for granted, aren’t a given for large parts of the world’s population. A truly impressive aspect was the rich Mayan culture, which is held in high regard in Santa Catarina Palopó. Almost all inhabitants are of indigenous descent, and the traditional Mayan language Kaqchikel is still in widespread use. The entire town is eager to preserve their heritage, such as crafts and herbal medicines. We learned a lot about the socio-political situation and history of Guatemala, as well as the worldview, traditions, and ancestral knowledge of the Mayan culture. These insights were a good foundation for the design thinking process by giving us an understanding and context of the existing obstacles. |

Define

|

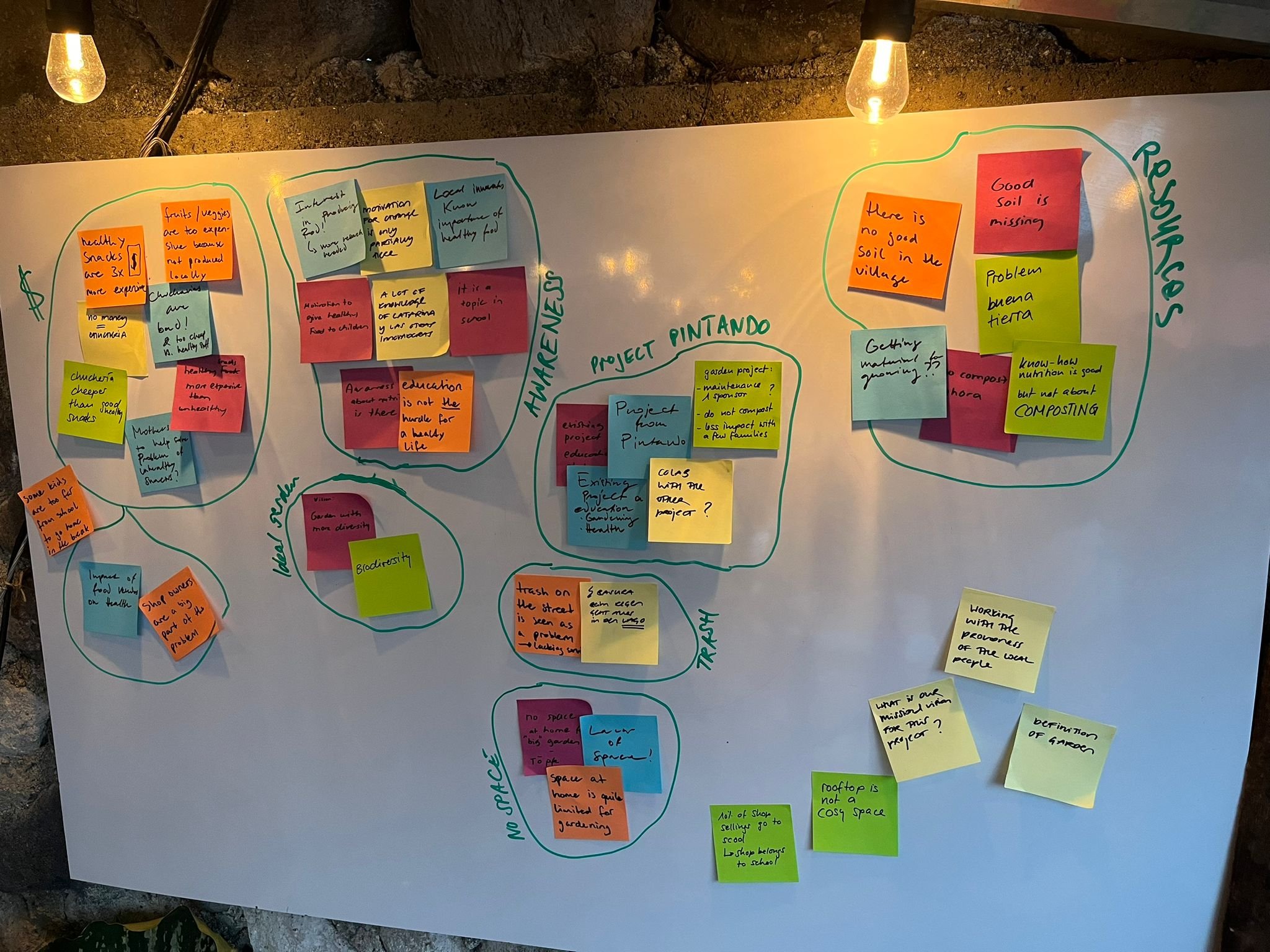

Five other participants and I formed the «equipo delfín», or Team Dolphin, with several local innovators – a group of women from Santa Catarina Palopó. Our task was to create a concept for an educational garden to promote circular systems, ecological sanitation, and healthier living. The aim was to lay the groundwork for a more resilient and independent food production and enable the community to share knowledge in sustainable gardening and farming. We started the problem framing process with interviews, workshops, and field trips, following the principle «observe – ask – try». This helped us identify and cluster the pain points and wishes the community had with regard to gardening and healthier nutrition.

Clustered pain points and wishes It was evident from the beginning that there was a genuine desire among the local community to maintain private vegetable and herbal gardens. On the one hand, it was considered an ideal means of preserving and passing on ancestral knowledge about herbal remedies. On the other, malnutrition is not uncommon in the community. Especially local kids eat unhealthy «chucheria» snacks, as these often are the cheapest option. The local innovators hoped that producing vegetables on their own would alleviate the financial burden of providing nutritious food to their children. The problem framing process quickly uncovered the major obstacles. One was space. Although Santa Catarina Palopó only has about 5000 inhabitants, it is quite densely populated, leaving little room for private gardens of usable size.

Furthermore, necessary resources such as good soil and fertilizer can be hard to procure or high in cost. And lastly, the local women in certain aspects lacked confidence in their own skills, for example, when it came to utilizing fertilizer, which traditionally is the responsibility of men. |

Ideate

|

With the key findings of the «Define» stage in hand, we started the «Ideate» phase by formulating the question «How can we use the existing spaces and provide solutions for sustainable gardening in order to help the people of Santa Catarina Polopó grow their own vegetables and herbs?» We approached these problems from many angles and came up with a lot of ideas, as the design thinking method prescribes. In the end, we narrowed the collected suggestions down to three deliverables: First, a concept for a school rooftop garden that addressed the lack of space in the town. Second, an easy-to-build worm box – a circular system that turns organic waste into humus that provides nutrients to the garden soil. And third, a concept for a workshop in which newcomers are instructed on how to build and maintain a worm box. |

Prototype

|

The strong focus on prototyping is a signature component of the Stanford model. Of our three deliverables, the worm box and the workshop were the most suitable for experimentation. Especially the worm box went through several iterations until we produced a model that proved satisfactory in terms of simplicity and durability.

Worm box prototype |

Test

|

Finally, we handed over the deliverables to the organizers, Mosan Sanitation Solution and Link4 Guatemala, so they could be tested in everyday conditions. The worm box has been met with enthusiasm, and in true design thinking fashion, has already been improved further by its users. |

Conclusions

|

It was a great experience to see how well design thinking methods work across cultural boundaries to tackle fundamental problems. If we can work out solutions in such a context, I am sure design thinking tools are a powerful means for creating and optimizing products and services for our clients (and we don’t need to speak Spanish or even Kaqchikel). My personal take-aways from this intercultural design sprint were: Do not assume but ask instead: We often tend to assume things from our point of view, but the experience of our counterpart might be totally different, even if you share the same cultural background. Simplify solutions whenever possible: Do not try to cover everything in a first draft and focus on the main topics. Listen carefully and let conversations flow: Not all people answer a question with their most important points directly, sometimes it needs some turns to come to the core. |